The Indonesian government banned catching Manta rays in 2014, following their listing on Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) Appendix II in 2013. An SCF-funded project has been assisting fisher communities find alternative livelihoods and food, to turn regulation into on the water conservation.

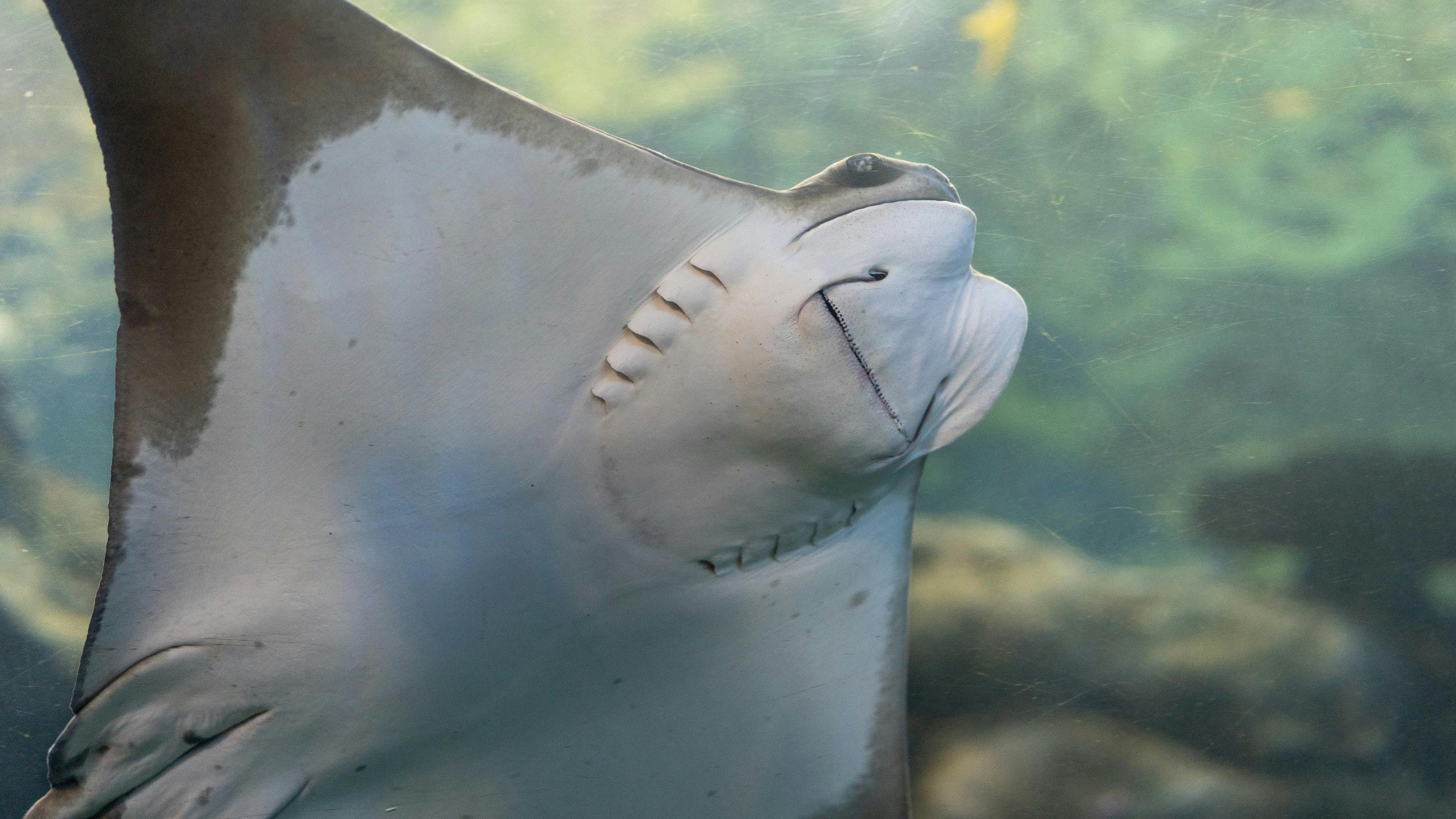

Mantas are one of the true marvels of the ocean. The largest of the mobulid ray family, the giant manta’s wingspan can reach more than seven meters. Like other large marine species, they live a long life and have slow reproductive rates, giving birth to only one or two pups every 2-5 years. This makes them particularly vulnerable to overfishing.

In 2014, Indonesia introduced sweeping new laws giving full protection throughout the life cycles to both species of manta – the giant manta (mobula birostris) and the reef manta (mobula alfredi). It became illegal to use any part of the animal even when accidentally caught, except for “research and development”. It effectively created the world’s largest manta ray sanctuary, with fishing banned across Indonesia’s Exclusive Economic Zone, an area of ocean about six million square kilometres in size.

One of the factors that convinced Indonesian authorities to act was the economic case for the value of mantas to the eco-tourism industry. Indonesia is one of the world’s top spots for manta watching. As well as being physically breath-taking, mantas are intelligent and curious creatures, making them a major attraction for divers and anyone who loves the ocean. According to a 2013 study, a single manta ray might fetch five to six million rupiah (US$350-420) at market, while a living animal could make up to 12 billion rupiah for the tourism industry over its lifetime.

But what if a community does not wish to embrace organised tourism, and all the impacts that it means, fearing it will undermine social values? This was the case for the remote island community of Lamakera, where the Shark Conservation Fund has supported a project showing that conservation is as much about people as it is about fish.

Hunting mantas was a long-standing tradition in Lamakera on the remote tip of Solor island. The species are commonly found in the plankton-rich waters around this island chain, and people rely on the sea for their livelihoods due to the relatively barren nature of the island’s soils. The mantas were hunted mainly for food, but from the early 2000s, growing demand for their large gills for use in Chinese medicine meant lucrative business for the manta fishers.

Indonesia’s 2014 catch ban meant that in one fell swoop, Lamakera faced losing not only a customary food source but also much-needed income. Enforcing the ban therefore proved to be a major challenge, and risked sparking understandable local tension. Efforts initially focused on preventing the trade in manta ray gills by focusing on uncovering smuggling activities and arresting culprits. But it soon became clear that additional approaches were needed.

Funded by an SCF grant, the Wildlife Conservation Society and local NGO Misool Foundation began working to help the community develop new sources of income and target different fish for food. The community was given a purse seine fishing boat, complete with nets, worth 800 million rupiah (US$56,700), and local fishers were trained to use the vessel to catch different types of bony fish such as tuna, marlin, snapper, both as a food and an income source. The fishers were also provided with cool boxes and an ice machine to keep the fish they catch fresh. A “sustainable fisheries collective”, or cooperative was established, through which villagers can borrow money and receive a share of profits.

More than 100 members of the Lamakera community have so far signed the pledge to never hunt manta rays that is required to join the cooperative. In addition, further projects have supported training local women to weave ikat[traditional cloth] and make tuna fish floss as new sources of income.

This multi-faceted approach, together with genuine community engagement and support, has yielded results. Catches of the giant manta in Lamakera fell by 91.7% between 2015 and 2018. As more species of shark and ray are subject to trade restrictions, similar work in coastal communities will be necessary for effective implementation.

A message from SCF Executive Director Lee Crockett: “Some of the most important work that SCF supports is with local fishing communities. Policy-change and enforcement of regulations are vital too, but if people are not supported to find alternative sources of food and livelihood, then eating and selling endangered sharks and rays will remain attractive. The project we funded in Lamakera is a powerful example of this simple truth, and of the innovative approaches needed to help conserve sharks and rays in a developing country.”

Please help us support similar work with your donation.